Colin Muller, Chief Executive, Muller Property Group gives advice to farmers and landowners on how to get planning permission on land.

I’ve written several articles on how to get planning permission on land, and hopefully offered pearls of wisdom and some firm guidance to those with farm land on the edge of towns and villages.

The overriding message I always give landowners is “get your cap in the ring” – its simple really.

The plain logic is, if you do nothing, if you are not active in pushing and shoving your land, then somebody else will get there first.

The truth is I’ve achieved planning permission for hundreds of farmers on land all over the UK, in a career spanning almost 40 years.

I always see every landowner myself, look at their land and then we do background research, before giving any view on prospects, and in advance of outlining a strategy and programme for planning promotion.

If you are dealing with a farmer’s life and main asset, which land is, being thorough in looking at the opportunity must come first.

This is combined with my experience of land of all shapes and sizes, and having dealt with the different stages of the town planning and appeal process on farm land in 60 or more local Council areas.

I reckon I’ve seen most permutations of how planning permission has been obtained but there are some general pointers I can offer.

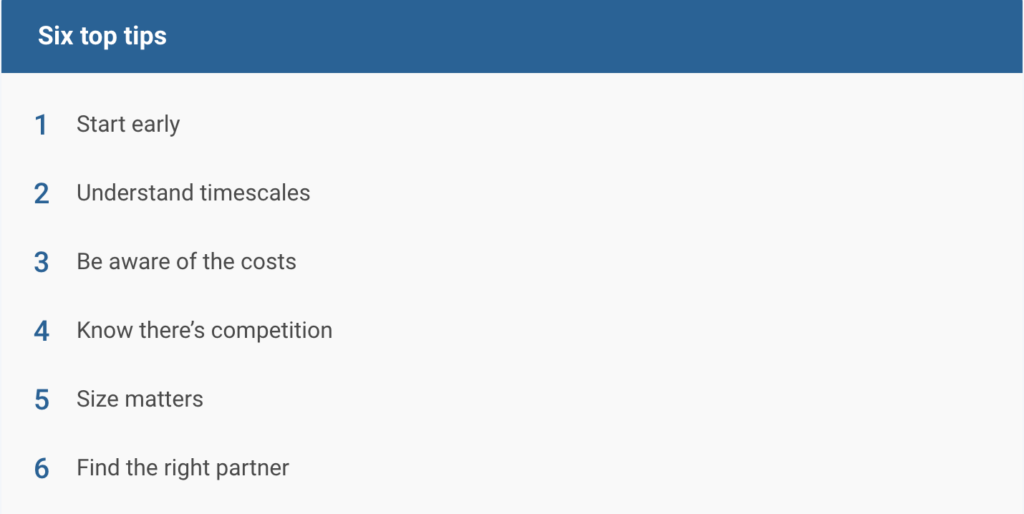

Start early

Some say getting planning permission is an art not a science, either way, you have to start early. The Council’s Local Plan is the guiding policy document that focuses on selecting land which then makes allocations for housing and employment.

It’s important to be a part of this process, and make sure you don’t miss the boat. Local Plans come around for preparation or renewal every 10 years and normally plan ahead for 20 years.

Councils often run a call for sites process in the early stages of a Local Plan so that’s a good time to be pushing a prospective candidate site in front of the planners.

The point about starting early is that there’s plenty of time to get “your ducks in a row”. Councils are only interested in finding and allocating land that can deliver development, so an early start means issues can be resolved well before any submissions have to be made.

Understand timescales

Explaining the planning process and the procedures and timescales involved in obtaining planning permission is not a favourite part of any conversation with farmers.

That’s because the system of plan making is bureaucratic, long winded and formulaic. It normally takes five years or more to make a Plan from start to finish.

By way of example, and believe me it’s a typical one, Cheshire East Council started their Local Plan in 2010, (it was a plan to cover the period 2010 to 2030), and it was finally approved and adopted in 2017.

Who would believe it could take that long, but then there’s no commercial or business thinking inside a Council, and no real accountability.

Relying on the Local Plan process alone for making an allocation on land you are promoting is long winded but has to be gone through as part of an overall strategy of getting land allocated.

The planning application timetable on the other hand is a bit more refreshing and should generate quicker results.

The timing for making an application needs to be looked at carefully and there are a host of factors to consider, but it’s possible to see it through in about 3 years.

There’s really no quick fix to getting planning permission and the local authority system is slow and cumbersome; the only ray of light remains the governments drive and commitment to produce 300,000 houses per year.

This focuses the minds of Councils who must now at all times prove they can demonstrate a 5 year housing land supply, whilst also meeting the government’s Housing Delivery Test introduced in 2018.

Another bit of good news on cutting down timescales is the new planning appeals process which has set a ridged timetable for getting appeals determined.

This means that barring any intervention from the Secretary of State (exercising his call-in powers to determine the appeal himself) most appeals can be done and dusted in twelve months.

Be aware of the costs

Promoting land, is without doubt a costly business. It’s mostly down to what has to be done to prove an area of land is suitable for development and show it is capable of being brought forward.

Councils are only looking for areas of land that they can guarantee will be delivered through their Local Plan or the grant of planning permission.

It’s now the norm for Councils to expect land to be shown that it is technically capable of being developed, and we must conduct the necessary surveys, investigations and proving work upfront which demonstrate there are no barriers to the Council granting planning consent.

Of course, there is a list of what Councils expect which is as long as your arm. Generally, it’s termed the ‘validation checklist’, and in most local authorities it spans to about 30 or so items.

The costs of making a planning application depends on the size of the site. A fairly straight forward planning application on a site of say, 10 acres, usually costs around £150,000.

If it is refused or the Council don’t consider it, then it will need to be taken to appeal, which means the appeal cost will be the same amount again – all in as much as £300,000.

This sort of upfront investment is significant, especially when you consider that there is no guarantee of success. My maxim is much like the lottery you have to be “in it to win it”.

The reality is the vast majority of landowners just cannot risk that sort of money and it falls on others to take the calculated view on win or lose on a particular area of land.

Know there’s competition

It’s never a ‘one horse race’, and this needs to be grasped from the off. Too many landowners get blinkered into thinking theirs is the only area of land in the game.

I’d say in most towns there are 20 to 30 competitor sites around the edge of any settlement and that would be mostly greenfield land not including additional sites in existing use (brownfield) inside the town boundary.

Councils operate a land vetting procedure known as SHLAA – Strategic Housing Land Availability Assessment, which sifts through all sites put forward by owners, builders, agents and land promoters.

In my view its not an all together reliable procedure as its subjective on the Council’s part, who categorise land as suitable or not suitable, developable, and whether it is available.

With so many sites vying for poll position it’s a ‘beauty parade’, and the Council only need a certain number of sites to underwrite their land supply.

It goes without saying that the land areas which are presented to the Council in the most professional, thorough, and technically resolved manner will find favour and move toward the top of the pile.

As I repeatedly say to all landowners, it’s a job that calls for specialist expertise, a big chequebook, and hardnosed resolve to see the job through and one that needs the will to blow the competition out of the water.

Size matters

There’s a twofold meaning where size is concerned – the size of the Council area in which the subject land falls, and the size of the site itself. Each Council has to meet its need for housing and employment provision.

There is a predetermined quantum of housing known as Objectively Assessed Housing Need (OAHN) for each local authority, and across the 404 Councils in the UK this can be as little as 160 dwellings per annum and as high as 4450 dwellings.

It follows that there is a better prospect of promoting a site for development and getting planning permission where there is a higher level of housing provision required.

Councils try and secure a range of site sizes, some large scale upwards of say 250 houses which would normally be housing allocations in their local plan and smaller sites of 50-100 houses which may come forward as planning applications.

Crafting the right scale of development proposed is important: there’s no point in being greedy. All greenfield edge of settlement sites will be assessed for impact and this will manifest itself in a variety of tests; landscape character, traffic, noise, pollution, wildlife and ecology.

Politics plays a part in where Council’s guide development allocations and local councillors won’t be favouring big chunky housing sites in their own back yard.

Councillors like to push development into locations where there’s the least line of resistance from local residents.

The bigger the site the more complaints that surface, and in most locations, there are now Neighbourhood Development Plans, which in the main are ‘anti-development’ formulated by local NIMBYS.

Size matters when it comes to it, and will have an impact on the chances of success, with smaller sites of say up to 10 acres sneaking under the radar, and the bigger ones getting caught up in refusal and the planning appeal system.

Find the right partner

Right at the heart of the matter is finding a skilled and experienced partner you can get on with. No point in choosing the nicest looking one with the slickest presentation who’s been wheeled in by the local land agent.

What’s required is a hardnosed no-nonsense campaigner with a track record of success. To obtain planning permission you will need experts who have the resolve, the tenacity – and the budget – to see it through.

The costs of promoting land for development are not for the faint hearted and you need a big chequebook just to get to the starting line.

You need a partner that is committed from the word go and whose focus and energy is dedicated to your particular piece of land and one that’s not compromised by having half a dozen sites in the same town.

Any sort of land promotion be it a soft local plan call for sites submission, or making a formal planning application needs to be driven.

Every site needs its own unique planning strategy with a sponsor and a figurehead who is accountable.

Landowners should be dealing with the organ grinder and not the monkey in whichever partner company it selects.

There are a lot of firms out there in the wider property market, builders, developers, and land promoters alike who claim to be doing the job of getting planning permission on land.

However, when it boils down to who in those organisations is actually dealing with a farmer’s prime piece of land, invariably it turns out not to be the main man, instead it’s a land manager who in the bigger companies move on at regular intervals.

My advice on finding your ideal partner is to look at the main movers and shakers in any particular business and what their interest is in that business.

If you are dealing with an owner of the business you know that it is his/her money and chequebook, and they are the decision makers.

That’s critical when it comes to having money invested in a project because they wouldn’t be in it if they didn’t believe in the chances of success.

As it’s their money, they are likely to stick with it come rain or shine. Furthermore, the benefit of dealing with an owner/managed business is that decision making is clear, instant and reliable.

We’ve been helping farmers and landowners to maximise the value of their land for almost 20 years and it’s good to share our specialist advice and help. You can see the full article in Farmers Weekly.

For a no-obligation initial assessment of your land, contact our land and planning experts at 0800 788 0900 or muller@muller-property.co.uk.